People

Dr Gossett’s residency has two proposed outcomes:

1. An intensive graduate seminar on abolition and trans aesthetics, archives and visual culture. The syllabus Dr Gossett co-authored with queer art history professor David Getsy on trans and non binary methods for art and art history would be one object of study, as it makes an intervention in both disciplines and touches on abolition as a central theme. Students in this seminar would engage with the work of Tourmaline, Wu Tsang, Riley Snorton, Micha Cardenas.

2. A public talk at the University that could hopefully bring into the fold both community members and other departments and relevant disciplines – such as history, queer theory and trans studies, Japanese-American and Japanese and Asian diasporic studies (in the Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies and beyond), as well as science and technology studies and interested graduate and undergraduate students. The talk will focus on queer Japanese American AIDS activist, Kiyoshi Kuromiya. The archive is at the center of this project, as Dr Gossett has done extensive research consulting archival material at the William Way LGBT Center, Stanford University, and the New York Public Library AIDS activist collection, where footage of his funeral is held. What follows are some key biographical pieces of information about Kuromiya’s life and work.

Born in Heart Mountain, Wyoming in an internment camp during World War II, he grew up in the securitized and militarized setting of the camp where his family was held for three years. Dr Gossett situates Kiyoshi Kuromiya within a political genealogy of resistance – including abolition – that both precedes and exceeds him. Kiyoshi Kuromiya’s uncle, Yosh Kuromiya, was not released, but rather, his incarcerated extended past internment to a federal penitentiary on McNeill Island in Washington State for his refusal to disavow allegiance to Japan and his involvement in organizing at Heart Mountain camp. Yosh’s refusal was not an act of cultural nationalism; instead it rejected the very imposition and problematic of a cruel paradox serving as justification for incarceration. This rejected and refused question was an example of what Lyotard termed the differend –as he could neither express nor forgo allegiance to a sovereign country to which he had no relation as a political subject.

Upon release Kuromiya’s immediate family moved to Monrovia, California – a suburban town. A precocious Kuromiya discerned he was queer while reading the Kinsey Reports at his local public library. Also as a child, he was arrested several times for cruising in the local park and placed in a psychiatric institution, a result of the fact that queerness was at that time pathologized and medicalized. Kuromiya ran off to Philadelphia, where he attended the University of Pennsylvania as an undergrad majoring in architecture. Kuromiya participated in the sit-ins with the Congress for Racial Equality in 1962 in Maryland and, while leading a group of high school students in Martin Luther King Jr.’s march from Selma to Montgomery, he was severely attacked by armed police and hospitalized. Photographs of the bloody scene as well as of Kuromiya marching with King, Reverend Shuttlesworth and others by pre-eminent civil rights photographer Jack Rabin are held at the Pennsylvania State archives. In the 1960s and 1970s Kuromiya was part of the homophile movement – participating in the Philadelphia Annual Reminders from 1965 onwards – and, following that period, the radical queer movement. He was one of the authors of the ‘third world gay liberationist’ manifestos that emerged out of the People’s Revolutionary Convention convened by the Black Panthers in 1970 at Temple University, a document that included a demand for sex changes and hormones for all trans people who wanted them. Kuromiya helped to start the Philadelphia Gay Liberation Front and during this entire period was surveilled under COINTELPRO and placed on the national security index.

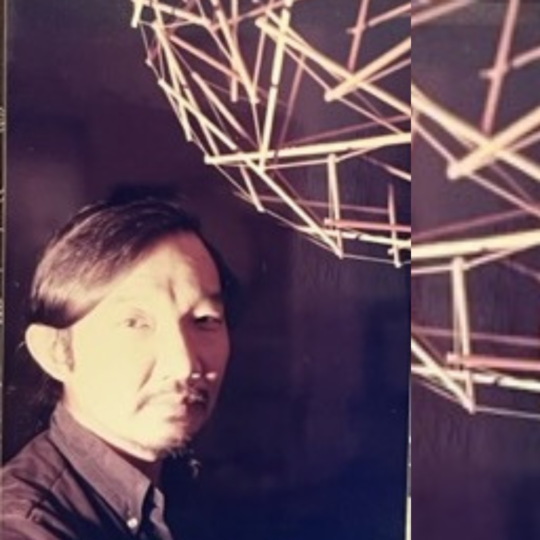

In 1977, while hospitalized with metastatic cancer, Kuromiya met Buckminster Fuller. This meeting began a collaboration that lasted the rest of Fuller’s life, but also initiated a critical intimacy that extended beyond Fuller’s death, through the posthumous editing, care and publication of his work, as well as his relationship with the extended family. Kuromiya was very close to the Fuller family and helped to transport the coffins of Fuller and his partner Anne from California to Massachusetts after their deaths – which occurred within days of each other – in July of 1983. Having worked with Buckminster Fuller from 1977– serving as his confidant and editor for Critical Path (1981) and the posthumous text published in 1992, Cosmography (Macmillan, 1992) – Kuromiya began the institute that continues to be at the core and heart of his legacy, the Critical Path AIDS Project. Rather than merely recycle Fuller’s grand technocratic and utopian visions of planetary scale, Kuromiya democratized Fuller’s ideas through a scientific and technological praxis rooted in AIDS activism. Kuromiya put the early internet to use for ‘PWA’s (people living with HIV/AIDS), including incarcerated PWAs in Pennsylvania and was co-author of the first standards of care for HIV/AIDS.

Kuromiya’s use of the internet, made free and universally available – freed from paywall and private companies for use by people living with HIV/AIDS – via the Critical Path AIDS project, enabled project’s newsletter and the bulletin board enabled lifesaving health information to be circulated not through the slow temporality of academic journals or medical and institutional bureaucracy, but rather according to the urgent and pressing needs of patients and activists struggling against premature death from HIV/AIDS. This meant that patients were able to access and exchange information about drugs and resources to keep each other alive. Kuromiya also put the law to use through his involvement in legal struggles against internet censorship, through the legal challenge to the Communications Decency Act, which aimed to regulate and censor “patently offensive” material online. “I don’t know what ‘patently offensive’ means in terms of providing life-saving information to people with AIDS, including teenagers” argued Kuromiya. The Communications Decency Act was struck down and would have foreclosed the possibility for sex education online during the height of the HIV/AIDS crisis. Kuromiya’s politics of care also extended to the everyday, as he provided hospice care for those dying with AIDS and a community chest for HIV/AIDS patients to have access to drugs at no cost and ran a twenty-four-hour HIV/AIDS hotline.

Kuromiya’s biography dramatizes how queer and trans activists of color have been involved in social movements that are often considered disparate and how these same activists brought an intersectional politics and an abolitionist analysis of gender and sexuality to bear on these various movements. Abolition as a thread sutures together each iteration of Kuromiya’s transversal political trajectory – from queer/trans liberation from cages and closets, to being in solidarity with the struggle against the structuring antagonism of anti-blackness and the afterlife of slavery – as seen through his organizing against American apartheid (segregation) during the Civil Rights and Black Power Movements – to his activism for HIV decriminalization and inside/outside incarcerated AIDS activism as part of ACT UP Philadelphia.